Listen to the audio file of this session (MP3 format)

Transcript

Session 1 – Introduction to The Great Re-Think

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Ian Rappel: Colin, hello. What we want to do with this session is to talk about the basis, if you like, of the College, College for Real Farming and Food Culture, but also broaden that out to look at the work of the Real Farming Trust and most especially your development of your ideas and the development of the College as an extension of that. I wondered if you could start then, by giving us an overview of your most recent work, which is a great rethink.

Colin Tudge: The idea of rethink basically, is to make the world a better place. And the observation is that the world at the moment is in an absolutely terrible state, which I don’t think anybody would dispute, on every front: ecological, economic, political, personal, mental health. Everything really, really, really seriously in a mess. And the point is, it doesn’t have to be like that. And if only we did relatively simple things well, as it were, we cooperated and so on, and so on, and so on, we could expect us, the human race, to live perfectly well for at least another million years, and probably several million years, but start off with a million. And as things are, we’ll say, many, I mean, not just me, but lots of people are saying, you know, we’d be lucky to get through the next 100 years in a tolerable state. And it isn’t just us, it’s the whole of the natural world. So what I’ve tried to do is to define what it is we’re actually trying to achieve in this world, what’s the goal, and I’ve suggested that what we should be trying to do is to create convivial societies with personal fulfilment, because our society is actually made up of individuals. And if the individuals are not happy, content, etc, fulfilled, then, you know, there’s not much of a society, but within the context of a flourishing biosphere, that all three things are important the society, the individual, and the whole living world best called the biosphere.

Now, a few little points here, it’s important to get the balance right between the three. If you have, I mean, there have been various political systems over the years, where people have been emphasised the importance of the society, but at the expense of the individual. And I remember the film actually of Dr. Zhivago, the leader of the Bolsheviks says, “Societies matters, the individual doesn’t matter.” And one of these chaps, one of his rank, and file says, “What does matter? Comrade, I’ve forgotten.” And I thought, that’s a very strong line. Because if the individual doesn’t matter, what does matter? But we’ve got to get all three right.

There have been other societies where people emphasise the importance of the individual, but forget the society as a whole. And I would say modern America is like that. That’s the crux of the economic system known as neoliberalism. It’s all about the individual and it’s about the material well-being of the, of the individual. Donald Trump is the sort of apotheosis of this, I mean, the epitome of this. And that’s vile. And of course, most political assistants, most standard political systems, forget the living world. And they regard the living world whether it’s an extreme left wing or extreme right wing, they tend to regard the living world as a given, as our property, we can do what we like with it. A terrible, terrible, terrible attitude. If we do that, well, it’s evil on many fronts, but we’ll be talking about that as time goes on, I guess. We’ve got to get all three right in balance. And the question is, how you do it, and what we actually have to do.

Ian Rappel: So you talk in your book about the idea of Renaissance. Can you explain to me what you mean by that?

Colin Tudge: Well, Renaissance of course literally means rebirth. And I started with the idea that in a way, we need to draw a line and start all over again and examine every idea that we take for granted. And everything that we do and take for granted, reexamine it from first principles. Then Renaissance, there’s basically I’m suggesting three ways to change a society, or three ways which have been tried.

One is simply reform, where you try and change a little bit and hope that it will have a big effect. Reform shouldn’t be written off. I mean, you could do very, very good things with reform, um, slavery was made illegal in Britain in the early 19th century and in America in the mid 19th century. Doesn’t mean it stopped, but it was made illegal by reform. And women’s suffrage was achieved up to a point by reform. So you could do good things with reforms. But there’s a lot wrong with reform as a way of changing society. One is that it’s very slow. One is because it took decades to get any of these things through. And in being in America, you had to have a civil war, before you got the anti-slavery through. And the other the main thing is actually that whether you change the law or not, if you’re simply reforming, it depends on the people who are already in charge. So if you’re a reformer, or you’re trying to affect a reform, you have to persuade the powers that be as it were, that they have to change it. What always happens with reform is that reforms are nearly always behind what is necessary, and things go on very badly for a long time, before the powers that be can be persuaded that they ought to change, because they don’t want to change. Because in general, the people who are in charge want things to stay the way they are. Because after all, they’re in charge of it so they’re aware of it on the whole.

Ian Rappel: Is that sort of thing we see, for instance, around the sort of international discussions of climate change, for example. You have an urgency of an issue. A slow and clunky reform system that’s unable to keep up with it.

Colin Tudge: Exactly, and the question arises, certainly, in the case of climate change, whether you could ever catch up? And the answer is that doesn’t look like it at the moment. So it’s too slow, too uncertain, etc, etc. And it depends on the people in charge wanting to change.

The second way to affect big change is, of course, by revolution. And what that tends to mean is that you have a fight. You go out and you pick a fight, basically, with the powers that be and try to remove them wholesale, and change it for something else. Sometimes that’s the only thing that works because you can try everything else, and it doesn’t work. So in the end, you just have to say, enough’s enough. But very few revolutions, I submit, excuse me, work out the way that the revolutionaries wanted it to work out. I mean, you know more about Russia than I do. But I don’t believe that the revolution of 1917 or the chaps behind it, or the chaps who started in the early 19th century leading up to it, I don’t think they envisaged Stalin. But what it finished up with was 20 years of Stalinism. Or the American Revolution, there were people, even at the beginning of the radical revolution, in the wake of it, early 19th century, who said, you know, this hasn’t turned out the way we want it to at all. This isn’t what we were looking for. And it was already the corporates who were beginning to take over the whole show. And of course, the French Revolution ended in the terror. Very rarely works. And the Arab Spring, to bring it more up to date. I mean, it looked for a time as if the revolutionaries had one and we had a more democratic society being introduced, but how long did it last? A few months, a few weeks. And then it petered out. Usually it’s the case, or often it’s the case, that the revolutionaries haven’t clearly thought out what it is they really want to achieve. And also, they haven’t put the infrastructure in place that would make it possible for them to achieve it. So revolutions, if you’re forced into it, you’ve got to do it, but very rarely work out the way you want them to. So if reform doesn’t work and revolutions don’t work, what are we talking about? How do we make change?

What I’m suggesting is that we need this thing called Renaissance, rebirth. And it was summarised here in a little comment, which is always ascribed to Ghandi, and possibly he never actually said, but ascribed to him, that you must be the change you want to make. And what renaissance implies is that the society at large that wants to change simply starts to introduce the kind of changes that it wants. As an example, I’m going to argue later that we need for example, small farms, small markets and so on. Well, it is possible even in the way that the present world is with corporate power and all the rest of it, it is possible to set that kind of thing up. So the way forward is for people at large, not the powers that be, but the people at large, to make the necessary changes that they want to see happen, as best they can and gradually build on that.

The one other thing, which is where I think the College comes in, and where my own efforts come in, is that in order to make that work, you really do have to do a lot of rethinking. Because you have to, I mean, if you’re going to make a different kind of world, you have to introduce the right kind of infrastructure. And you have to work out exactly what the infrastructure is that you want, what kind of economy do you really want? What kind of governance do you really want? And underneath that, you have to say, what kind of moral stance do we want, and so on, and so on. So the thinking has to go from the top to the detail right down to the big generalisations or the other way round, you see what I mean? The thinking has to be at all levels. And it has to be very deep. And it has to be conducted by people at large. You can’t leave it to, as it were, the powers that be, because the powers that be have screwed it up.

Ian Rappel: Well, I think there’s two challenges to that position, if you like. One of them is you’re not suggesting that we, for example, stop our day to day struggle for improvement..

Colin Tudge: No, no, no. You do make the changes, as it were, in situ. And you build, even as things are, you build a better future, while at the same time you’re planning the next steps. The two things have to proceed together.

Ian Rappel: And that’s where something like the College comes into play, because it’s the creation of those spaces as were. Because the other element to think about, if we’re thinking of a complete reset of thought and everything, is that a lot of people are locked, for very good material reasons, locked into the existing system and short-termism, and in many cases are working their socks off, doing many jobs to try and keep going and everything else. So it’s the creation of the space for people to come off the treadmill to have a look at the issues in a fundamental way. And I suppose that’s how certainly how I see the College. Provision of those spaces of hope, if you like, or spaces of exploration and dialogue, so that we actually get a chance to bring people together who perhaps wouldn’t ordinarily be together into the spaces to debate particular issues and topics and then move things forward.

Colin Tudge: And not just debate, I hope, but actually create help to create the structures that will make things happen. And when we shouldn’t just be talking about small farms, for example, we should be setting them up, or helping people to set them up.

Ian Rappel: Yeah.

Colin Tudge: That part’s very important. It’s action and thought.

Ian Rappel: Yes.

Colin Tudge: I think we’re in dialogue, you know. One person does something, you think, etc, etc.

Ian Rappel: Yes, I know, they ought to have enough within them that they, even as we develop themes and discussions, we actually change ourselves as we process a kind of atmosphere of mutual learning.

Colin Tudge: And one thing I’m sure you’ll agree with: a lot of people who are, as you said, locked into a system, are doing things they don’t really want to do. And they’re aware that they’re doing things they don’t really want to do, like people who have enormous chicken farms, for example. I mean, I’ve seen farmers who were lured into getting bigger and bigger and bigger units, who absolutely hate it. They say, “This isn’t what I wanted to do, but it’s the only way I could make a living.” And so one thing is that they are indeed locked in because all their money is locked into it, etc. The other thing is that they are psychologically primed to want to do something else. And that’s important.

Ian Rappel: So the other question that comes up, and it’s related to that need for spaces, and it’s an area where I struggle a little bit with the Renaissance – I’m trying to sort of understand it – but it’s the confrontation of power. So we could, in theory, have lots and lots of really good discussions and start from first principles. But within society, if everybody is on that treadmill because of the way that society is structured by people, it’s not something that’s structural space, you know, these are policies. I mean, I read recently, I think Oxfam International said 85% of the world’s population are now living in under austerity. So it’s in that environment, as we’re trying to look at different ways of running the world, and in particular in agriculture and what the alternatives are, how can we at the same time challenge power? Because that’s the temptation for us to all feel good about ourselves as we talk about the alternatives. A bit of knowledge to translate that outwards into challenging power itself. I just wondered if you had any thoughts? I mean, it’s a tricky area.

Colin Tudge: Well, several things. One is, as you said, at the beginning, you need to create space in which people can actually change to some extent. On the other hand — so I think it was Lenin, who said (possibly was it Lenin?) who said all revolutions begin with the middle classes. He was middle class, of course. And the reason they begin with the middle classes is because the middle classes are the only people who’ve got any breathing space, because they’ve got spare money more or less, by definition.

But the other thing that strikes me is the extent to which working chaps and women who have nothing to spare apparently do manage to effect change. And I’m thinking, for example, guys, like Nye Bevin, who was a coal miner in a very difficult time, in the beginning of the 20th century. And he managed to summon up the energy to educate himself and became a very serious politician who founded the NHS, etc. At the beginning of the 20th century, both in Britain, and in the United States, there was a very strong sort of workers’ education movement. And it wasn’t just education, it was genuine action. And the point is, if people are really determined to do things, they can do it. I mean, it’s very hard. These people were heroes.

Ian Rappel: But what you’re suggesting is, is that there are already in place long established traditions of sort of forcing social change through any of those three routes – reform, revolution or Renaissance – but they depend to some degree on a kind of self-organising.

Colin Tudge: They do. They depend on people. Well, you do need people with exceptional talent, and exceptional energy. Like Nye Bevin, like Keir Hardy, who founded the British Labour Party, like quite a few Americans who would leave etc, etc. You do need those people. B you recently need the people at large to be onside and want to change things, and then things can change. And the one thing about the kind of change we need now is that there are so many people in the world who are aware of the need for change, and who need it to happen.

I think there was a study done and I can’t quite remember the reference. But it was sort of calculated something like 40% of the people in the world actively want the world to be different, and have a clearer idea about how it should be different. So you know, basically you’ve got billions of people potentially onside. But you’ve got you’ve got the establishment, really established centres of power, stopping them doing anything.

Ian Rappel: How does that relate to the idea of social movement? You know, if you’d like the kind of, because big figures like Nye Bevin and the others, you mentioned, have all been crucial. And there’s lots and lots of others, we could mention in history who have made that, you know, those differences, like Rosa Parks in America with the civil rights movement and that kind of thing. But they’re also they’re always within us within a social movement. They’re not just very clever individuals, they’re connected in many ways…

Colin Tudge: They create the social web as well. I mean, they are part of it, they help; the social movements are there.

Ian Rappel: Yeah. And it’s, again, going back to the College, I suppose. One of the elements of its work, if we can develop this, is to provide what you’ve called in the past, I think, a conceptual spine to the movement, allowing space to be developed to explore the themes and topics that effect in particular the relationship between food systems, agriculture, and all of this area of social change that we need. But it can provide that if you’d like a kind of a radical pole of attraction for social movements, to explore those things. I mean, it means giving up some of the definition of what you see as progress, because you’re democratising that element, aren’t you?

Colin Tudge: Yeah, we’re going to talk about progress.

Ian Rappel: That’s where I was going to go next!

Colin Tudge: Because at the moment, I mean progress tends to be – we’ve talked about conventional politicians or conventional views of things – people see technological change as progress. So as it were, GMOs, genetically modified organisms, genetically engineered wheat, and all that is seen as progress, because it’s technologically very, very, very clever. And money is seen as progress, as Liz Truss infamously said recently, growth, growth, growth. And increase in money, per se, is seen to be progress. And that’s not what we should be talking about. What I’m talking about is that we define the kind of world we want, what we should be looking for is to create convivial societies, personal fulfilment, and a flourishing biosphere. Now, I would suggest that movement towards that goal should be seen as progress. And in a sense, anything else is either marking time, or it’s going backwards. But basically, it’s a change of mindset to change the way you behave, change of thought, etc, etc, etc. And very small changes of technology does it – not, not necessarily very big changes, like you know, not genetically engineered crops, but just growing crops differently. And in ways that we know we can do in fact, agroecologically, but we will come to that. So that’s what I would call progress. It’s social progress really, and well-being progress and well-being not just human beings, either, but of creatures at large.

Ian Rappel: So how have we, in your view, got to the point where progress is measured by such crude numerics?

Colin Tudge: Well, it’s a very, very big question, which I will presume to try and answer, but only presume. I think it is to do with the nature of power. But if you want power, actually, you need – well, power is related to wealth to wealth, really. If you’re rich, you could buy all sorts of things like soldiers on your side, and machinery and guns and all sorts of things. In other words, wealth and power go together. And so the people who actually run the world are the people who are actually interested in power. And what they do to achieve power is focus on the things that will bring them power, like money, and then on the kind of technologies that will enable them to make their presence felt, like guns. So the world is run by people who want power. And what was your question again? Why they got into this mess? Well, the people who have got the power, call the shots. So you know, we have this idea of progress as being moving towards more wealth, more control over nature, etc, etc. And in a sense, why, because the people who are actually in charge, that is their mindset, or the rest of us reflect their mindset, because they’ve got the power. And they control the education, and they control the media. So it’s these ideas going around, which are bad ideas.

Ian Rappel: Going back to the goal: to create convivial societies with personal fulfilment within a flourishing biosphere. Some of that is, if you’d like, intuitively understandable, but I wonder if we could pick out a couple of words, and you could explain a little bit more in depth. So the first is convivial.

Colin Tudge: Well convivial literally means living together. And basically, you can’t live together unless you are getting on quite well together. So it basically means creating society in which everybody gets on quite well and has a reasonable time. You can’t do that – I’ll come on to this later, perhaps – but you can’t do that unless the people in the society want that to happen. And unless they actually give a damn about the other people in the society, which means they have to have something which is normally called compassion. So you know, there a convivial society has all these implications about it.

Personal fulfilment – you might ask why use the word ‘fulfilment’ rather than ‘happiness’. And lots of people talk about happiness. And the American Declaration of Independence starts off by saying every person has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Well, various things about that, but we’ll leave them for the time being. I think the word happiness has been much misused, and it tends to be in the modern world, at least, it tells us to mean hedonism, really. Bacardis on the beach and all that kind of stuff. But actually, if you pursue happiness, as many people have said, I think St. Augustine may have said it so well – good references here: pursue happiness, and you don’t really achieve it. What you want to do is what you should be looking for is fulfilment. And, for example, I don’t keep sheep myself, but I know quite a few people who keep sheep, and some of them keep them up on the hills. And they sometimes, you know, find themself delivering a sheep at three o’clock in the morning, with snow falling. And it’s horrible, you can’t think of a worse job. And yet, they love it. It’s what they do. And why did they love it? Because well, they feel fulfilled when they do it. And fulfilment doesn’t mean all happiness, it means, you know, often you suffer. And you can’t really be good at anything unless you practice and etc, etc, which often involves suffering. So fulfilment is the term, not happiness.

And the third thing, what was it? The biosphere. Well, again, when people talk about the natural world, they tend to talk about the environment. I hate the word ‘environment’ in this context. Environment literally means surroundings. And in the modern world, where we live in with the neoliberal economy, the material centric economy, it tends to mean real estate, you know. My house is worth a lot of money because it’s a nice environment. I’ve got woods in view, and all that kind of stuff. Well, that’s not what the living world is about. It’s not, for us our benefit. It’s not just what we do. It’s not just our surroundings. And so the word biosphere, on the other hand, literally means living world. And that’s what we should be aiming to achieve. Whether it’s good for us or not. Tthe living world is the idea, and biosphere is the word. If you want an adjective from biosphere, ‘biospheric’ sounds a bit weird. I’ve never heard anybody say it. But the word ‘ecological’ will do. Say, ‘Yes, we are in a mess, ecologically, not biospherically’.

Ian Rappel: We’ll explore all of those ideas in more detail in the next sessions. But just to go back, if you’d like to your vision, as it were, around the great rethinking: Can you clarify what you mean by starting from first principles?

Colin Tudge: Well, people get the get the word principle wrong, in my opinion, because people confuse the word principle or the idea of the principle with ideology. And ideology is an inferior thing. Really, ideology is just a description of how some people think you should be living and sort of things you should take seriously. So there are political ideologies, there are economic ideologies, and so on and so on. And it’s wrong, in my view, to talk about political principle, because that simply means the way the Tory Party or the Communist Party or whatever party it is, thinks you should behave. And the same would be true, even more true of economic principle, where you say you should do this, because we all know that we should be trying to maximise wealth, and so on. So that is the principle we should be working on.

But to my mind, then, there’s only two kinds of principle. And one is moral principle, which asks two kinds of questions: first of all, what is it right to do? What is actually good? And the second is, what is the nature of goodness? Which is a different kind of a question. Where does goodness come from? But that’s a sort of moral question. And that’s a principle. And the second kind of what I have genuinely called are ecological principles. Ecology asks, What is it necessary to do in order to live a life which is good? And also what is it possible to do within the limits of this planet? So put those two together, and you’ve got principles on which you can found everything else. And you can be asking from that, well, if we’re working from those principles, what kind of political system do we actually need that will move it and to embrace those principles? And what kind of economy do we really need that will move to embrace those principles. But they are the principles that should be driving the way we structure the society. We shouldn’t be trying to structure society, according to some political or economic preconception.

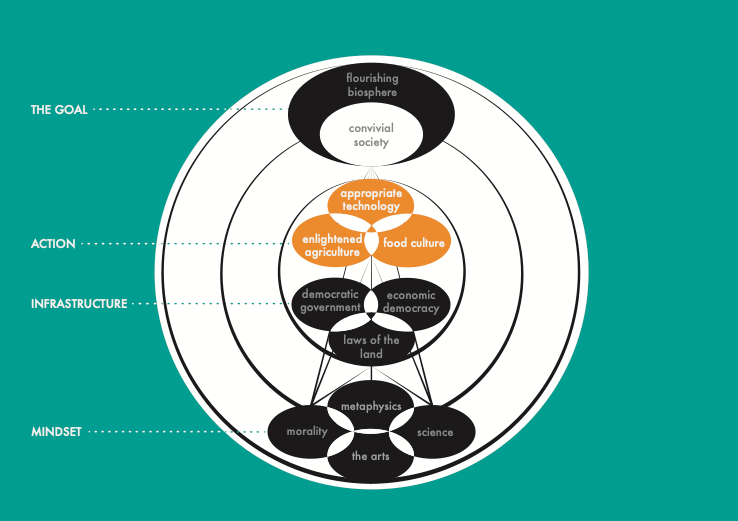

Ian Rappel: So calling to rethink everything from first principles sounds like a very tall order and would be very challenging as an abstract exercise. You’ve developed a diagram that can help us hang that.

Colin Tudge: Yes, the whole thing can be expressed in this very simple diagram, although the details are very complex. And basically, as you can see from the diagram, there are 12 balloons arranged in four tiers. And each balloon represents an area of thought that we have to think about. But the really important part of the diagram, although it doesn’t show very clearly, necessarily, are the lines that attach each balloon to every other balloon. And that’s important. So that although you have to think about lots of different things, in fact, I’m suggesting 12 different things, always think about everything in the light of everything else. And this really is what ‘holistic’ means: everything in the light of everything else. And so the whole idea is to develop a kind of holistic view of the world, and what we should be doing to put it right.

Let’s just go through the tiers, as I say, the balloons are arranged in four tiers. The top tier is marked ‘goal’: what are we trying to achieve? And as we discussed earlier, what we should be trying to achieve is convivial societies with personal fulfilment, within the context of a flourishing biosphere. I’ve suggested that in order to achieve a convivial society, you need people, basically to be cooperative. And you need people to give a damn actually about other people and about the natural world. And one question that arises very fundamental question: Are people capable of being nice to each other? Behaving morally? And do we really give a damn? And are we capable of sustaining this kind of mood? And pessimists, like, let us say, Thomas Hobbes, in the 17th century, concluded that we weren’t. And basically he said, unless you have people in charge or strong government in charge, then people left or life left to itself, just to ordinary human beings, will be – what’s the expression? Short.

Ian Rappel: Nasty…

Colin Tudge: Nasty, brutish, and short. Yes. Because that’s how human beings are supposed to be in his view. And Plato said something very similar, actually. And Locke said something very similar. I mean, it’s the kind of common view, and it’s a very common view. It’s an idea that’s very convenient to people who actually want to be in charge, because it gives them the excuse of being in charge, because it says, If we weren’t here to keep you locked in order, you would just be at each other’s throats.

The opposite of that really was expressed by Tolstoy, who wrote a very fine essay about anarchy, anarchism. And Kropotkin and said the same kind of thing. At the end of the 19th century, anarchism in Russia was a very strong idea, and basically said, look, if we ran our own affairs, life couldn’t possibly be worse than it is under the tsar’s. And we might be saying the same kind of things now, actually. So the question then arises, okay, it could be worse, but are human beings really capable of behaving well and looking after each other? If you look at many societies worldwide, living as it were in a state of nature, you find that they are convivial in this sense. I mean, there we are. There’s the proof, there are the people living that way. But also one of the guys who contributed or who wasn’t trying to contribute to it, but who did contribute to the idea that human beings are basically last year at each other’s throats, was Darwin, who in his book, The Origin of Species the basis of evolution put tremendous store by the idea of competition. And his idea, basically, was that evolution is driven by the need to compete. So I’ve come across in my time because biology is my thing – your thing as well, I think – a lot of people who sort of argue that we human beings are bound to behave badly because we are evolved creatures, and we are bound to compete with each other. And competition means you put the boot in, when you can, etc, etc, in the banner of let’s say, Machiavelli, which is what he recommended.

And the question is, is that true? I mentioned our Kropotkin, who was a contemporary of Tolstoy, more or less, but younger biologists, Russian biologist, who said, ‘No, actually, you know, I like Darwin’, he said, more or less. ‘But I think he’s wrong about this emphasis on competition, I think, really, human life in general, from which we might infer human beings in particular, life in general is fundamentally cooperative’. Nature, take it all, in all, is more cooperative than it is competitive. And if you look at nature, as a whole, or the cosmos as a whole, you can see competition and cooperation, like yin and yang, opposite sides, basically in the same coin, each dependent on the other. But you also find that cooperation is the thing that prevails. And if it didn’t, if cooperativeness didn’t prevail, then actually life would be impossible. The universe would be impossible, galaxies would be impossible. It’s because things work together, that anything at all important happens.

And if you look at us, our own bodies, the eukaryotic cell, the kind of body cells that we have, this actually turns out to be a massive sort of cooperative between various kinds of micro organism. And any kind of multicellular organism is a cooperative between different cells, each of which has the potential to go off on its own and do its own thing, in which case you’re going to have cancer. But that is a pathology. And it doesn’t happen universally. And of course, you get societies because creatures choose to work together or do work together. And you get ecosystems because the species interact fundamentally in a cooperative way, even though they are also competing. So one would say, look, actually, biologically, life is fundamentally cooperative. And for us to behave cooperatively doesn’t go forward in the face of nature. It’s actually what nature, that’s actually what we’re set up to do. So I like that I like the idea that behaving cooperatively is, as it were, natural. And there’s plenty of people who have said, well, you know, behaving naturally doesn’t mean behaving well necessarily. On the other hand, it’s jolly nice to have nature on your side, as a Catholics, for example, recognise this with the idea of natural morality. So that’s, that’s the first thing. We are capable of behaving convivially, in my opinion, well, lots of people’s opinion.

The second tier down is about action. In other words, what do you need to do physically, in order to achieve the goal? And I’ve suggested that all technologies are relevant. It could work in your favour, it could be work against you. At the moment, there’s what one might call or what I call uncritical technophilia. In other words, it’s kind of assumed in high places, that technological advance represents progress. So people in high places will look for a high tech solution before they’re really looking for what the problem really is. So it’s a question of deciding what kind of technologies really work. And what we need, I’m suggesting, is a much better, more refined philosophy of technology. Not simply asking how can we make bigger and better technologies, but how can we make technologies that really do what we want them to do? That really move us towards the goal of convivial society etc, etc, which some obviously do. And some actually don’t. I mean, one looks in context, let’s for example, look at a Bill Gates’s influence in Africa, where he is convinced the way forward for Africa is a sort of high tech solution, etc. And of course, the corporates love this because they’ll be making their money out of it. But we’ll hold the ground and ask is that what’s really appropriate to that place? Anyway, we need a better philosophy of technology.

The second thing I’m suggesting is that of all the technologies there are and of all human activities are, absolutely none is more important than agriculture. Agriculture is the thing you absolutely have to get right. And if you get it right, there is this possibility that the human species and other species could survive on this earth in a tolerable state for the next million years. Plus, if you get it wrong, no chance, basically no chance at all. And we’re getting it horribly wrong right now. So the priority is to ask what kind of technology what kind of agriculture will really take us to where we want to be. And we’ll be discussing later.

The other technology, which is of key importance, up there with agriculture, is, of course, food, and cooking, what kind of cuisine will take us forward, what kind of foods you will be growing, and food and agriculture – food culture and agriculture – have to work in concert. I mean, basically, there’s no point in farmers producing things, unless people at large want to eat them. And on the other hand, what people want to eat should be geared to what the farmers in that context can produce. And then of what you might call a traditional society, that is what happens. I mean, the society that’s cooking is geared to what farmers produce, in a modern society, not necessarily. I mean, you know, everything goes off in all kinds of directions, basically at the end driven by money and driven by what’s fashionable at any one time. And that’s nonsense. So we need a new food culture, we need to think about that from first principles.

Third tier down is infrastructure. And that is about how should we organise the society in order to make sure that we’re doing the right kind of things that will move us towards the goal, etc, etc, etc. And I’ve organised that I’m suggesting that we could discuss that under three headings:

The first is governance. Do we need government at all? If so, what kind of government do we need? How do we make sure we get the kind of government we need? How do we make sure we get rid of the governments that are not doing the job, etc, etc, etc?

The second thing we got to get right, is the economy. People get the economy horribly wrong. And they think it’s about including politicians who vote, they think it’s about making more money. In fact, the economy more than anything else, is the means the mechanism by which we could turn our ambitions – i.e., join to create a better society into reality. And the economy can either make it possible for us to do the things that need doing, or could get in the way. And I’m suggesting that much of the present economy gets in the way of the things we need to do in order to create a better society. But the economy is next. Note, if you would, that the economy – if we’re talking about what kind of society do we really want – has a moral dimension, and not just a technical dimension. That’s very important, but often not discussed.

And the third component of the infrastructure, in reality is the law. And we should ask whether the laws are of the right kind, whether they’ll lead us in the right kind of directions, are they enforced? Are they enforceable? If they are in if they are enforceable, whose job is to enforce them? And do they do it properly? Again, though, with the law, very obviously, it has this moral dimension, which is not often made explicit. And actually, in reality, you only really need laws when there’s any kind of doubt, if you see what I mean. I mean if you really want to prevent bad things happening, they should be unthinkable not simply unlawful, then we should not be. I mean, people at the moment sort of wreck the natural world. We got to do whatever they want to do. A lot of people are saying at this moment, there should be laws against this. Crimes against nature. But it shouldn’t be necessary to have a crime against nature. It should just be unthinkable that you would wreck the natural world. As in many societies, it has been in the history of the world. Particularly among people, of course, who live close to nature and who know that if you wreck the natural word, you wreck everything.

The last thing is this thing called mindset, which are all the ideas that are in your head, and attitudes, which you don’t necessarily think about at all, but you just take them for granted. And all knowledge, all those things that are just there. And you assume, and I’ve divided that into four areas. One is science, which is now a chief source of telling us what is really how the universe really works, etc, etc. The second is morality, which endeavours to tell us what is it right to do. The third is metaphysics, which is more or less gone missing. But many will say it’s the most important thing of all, it asks the most fundamental questions like what is the nature of goodness? And what is the universe really, like? But we’ll come on to that. And the fourth thing, under the heading of mindset is the arts, the arts just being tremendously important, because it’s the arts as much as anything that shape our attitudes towards things. And attitude is sort of nine-tenths of the law really, we don’t, when you take things seriously, or whether you don’t take them seriously, largely determined, dependent on how you look at it. And how you look at it depends on largely on the last painting you saw, the music you’ve been listening to, etc, etc, etc. So that’s it.

And the whole idea is you look at all these things, and an education that fails to look at all these things, is an incomplete education. But not only are you looking at them all, these 12 areas of discussion, but you’re looking at each one in the light of all the others. The economy has a moral dimension. So you’re asking the question, yes, but how do you know it’s true, and all that kind of stuff.

Ian Rappel: Thanks for all of that Colin, because I think what you’ve done is not just talked about the need for renewal, but actually provide us with a substance and a structure for us to look at the whole idea of renewal, renaissance and meaningful change. And I think what I particularly like about it is that within all of that structure, what shines through is optimism – that we are capable of that change, that it doesn’t have to be the case that we fatalistically have a world in front of us. It’s also not only going in one direction, we can actually be the agents of change. So thank you very much.

Colin Tudge: Good. Thank you.